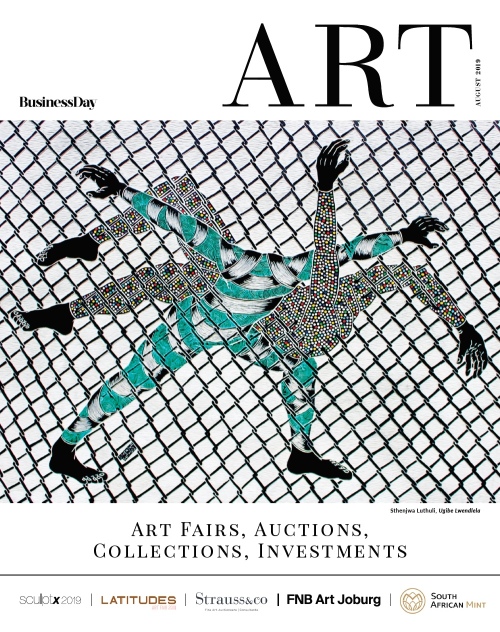

Artthrob.co.za

William Kentridge

William Kentridge’s latest exhibition ‘KABOOM!’ at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg is a large exhibition, which draws on work produced for his recent theatre performance projects. Audiences can expect to see many drawings, prints, animations from The Head & the Load, and Wozzeck, as well as some new sculpture on exhibit. This exhibition opens in the same month as some other significant Kentridge related events. One of his drawings reached an international record sales price of R6,6 million on auction, and Kentridge’s latest theatre piece The Head & the Load opening at the Tate Modern in London to mark the centenary of the First World War.

It can be quite easy to forget how significant Kentridge is internationally, as a highly regarded contemporary South African artist, because when he is in Joburg, he seems so accessible. His work is everywhere, the Centre for the Less Good Idea is open to the public during season, he’s spotted quietly minding his own business at art related events and around Maboneng, with a ready smile and tilt of the head for those who greet him. This exhibition at the Goodman Gallery is a window into the work that happens behind, and alongside, the major productions that make their way to the big museums, opera houses, universities, and art venues all over the world. It is a reminder of the larger workings at play.

William Kentridge Untitled (Drawing from Wozzeck 63), 2017. Charcoal on paper

Like most of Goodman’s Kentridge exhibitions in the past, ‘KABOOM!’ offers a great variety of visuals and experimental, expressive drawings for its audience. It affords insight into Kentridge’s process, and his mind, when you see the drawings that are both preparation for larger projects, and his determined production that stems from his research. This ability to provide access to the viewer is something quite unique, as quite often, we only see the curated, shiny, highly produced finished product of the artist. Not that the work isn’t ‘finished’ as such, but you can almost picture him at a wall in his studio with duct tape around the edge of the drawing, applying a bit of red conté, erasing a little charcoal, tearing up some archival document and gluing it to his paper with a fine brush. The tactility, motion and expression in his work renders it lively, the mark-making precise, yet free.

As is expected, the canon remains the same. Some of the details, or the images change, and it’s evident that Kentridge has new obsessions and curiosities, and has been reading new material, but thematically, the work still considers the same subject matter from different perspectives. The undertone in his work still confronts colonialism, and its long-lasting after-effects, but it’s insinuated rather than clearly depicted. The danse macabre that Kentridge has been employing in his stage productions, and the absurdism in sound poems such as Ursonate by Kurt Schwitter (1932) that he draws inspiration from, emerge strongly in his visuals.

William Kentridge Drawing for The Head & the Load (Fallen Figures), 2018. Charcoal on paper

When considering the period between the early 1900s, the advent of the First World War, and all the way into the Second World War, there was an efflorescence of absurdism in the art world. Marcel Duchamp, Cubism, the Dadaist movement, German Expressionism, and Surrealism, among many other distinct, or overlapping movements in Europe, had a great influence on the thought processes related to cultural production, not the aesthetics alone. These movements inspired a great amount of literature, political thought, musical expressionism and grand philosophical declarations. They were mostly counter reactions to the horrors of the wars, of the death, the starvation, the hatred, and the mobilisation of fascism. It seems almost inevitable that Kentridge, who has already related so deeply to these movements and their philosophical explorations, should focus on the First World War and the contribution that African soldiers made, fighting for their colonial powers.

There is a crossover between landscape, and body in landscape works like Drawing for The Head & The Load (Fallen Figures) (2018) wherein the deceased become the hills themselves. Maps are frequently used to complicate the images, showing extra levels of chaos and confusion, abstraction manifested physically, and intellectually, because maps represent so much about the way things happened, and the way land was perceived, instead of being the factual documents we expect or assume maps to be. This can be seen in works like Untitled (Drawing from Wozzeck 63) (2017), in which one sees the mangled structures that used to be buildings, an aesthetic echoed in works that look like aerial view maps with pathways, but simultaneously like barbed wire.

Kentridge deals with fragments in his works on exhibition at the Goodman. The drawings are moments in time from the greater narrative, humanized, and drawn from the perspective of the singular heart, or mind. His work reflects the chaos and the media of the Dadaists, using collage, bizarre combinations of words that form a strange poetry on the page, covered in drawings that emulate barbed wire, it emphasises the banality of war, and evades the temptation of overarching narratives, focusing on the local, the individual and the personal. The fragmentation gives opportunity to present multiple histories, as in the production of The Head & The Load itself, there are innumerable voices speaking, shouting, singing, laughing, crying, ululating, through his work.

William Kentridge Drawing from The Head & the Load (L’Impot du Sang) , 2018. Collage of printed text, charcoal, pastel and red pencil on paper

His work considers how narratives are told, and retold, throughout history, how the past is fragmented and subjective. Histories are multiple, complex and often contradictory tales of experience, sometimes told with the intention of telling particular versions that suit the victors, abandoning stories of the individual in favour of the overarching theme the writers of history wish to portray. In Kentridge’s work there are always many voices, visible in the sometimes chaotic scenes in his theatre performances where many strains of music, numerous voices and arbitrary loud sounds intersect to form its own absurdist ‘sound poem’.

For all the darkness portrayed, there is a kind of magic drawn out in his work, that speaks of human nature and how it is possible to find laughter and humanity in the absurdity, chaos, and darkness. Emotion, experience, history, understanding, memory – these are never linear, or definable experience with objective clarity, but complicated and abstract. Kentridge’s work is homage to this, to the individual, to the humans that lived through immeasurable difficulties at the hands of those that wrote the history books. These archives are torn up, repurposed and reorganized, drawn over by Kentridge, in an effort to lend a voice to those who would otherwise recede and be forgotten, recreate memories, and to remind all what is at stake for the average human when things come to a head between those in power. There’s something particularly poignant in globally politically turbulent times, all things considered, about the use of The Head & The Load as a play on the Ghanaian proverb, ‘the head and the load are the troubles of the neck.’

Download PDF: The Troubles of the Neck – William Kentridge’s ‘Kaboom!’ by Nicola Kritzinger

-26.149340

28.033780